Central Bank Digital Currencies

And the Social Nature of Money

You’ve probably heard some of the fuss around central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). This article is neither a fiery condemnation (that would be too easy) nor a technical explanation, nor anything in between. I will briefly explain what they are, describe their attractions and dangers, and then explore some seldom-discussed foundational questions.

What is a central bank currency—digital or otherwise? It is money issued by a central bank such as the Federal Reserve that either circulates as cash or is held in accounts at the central bank. Today, the only entities that have accounts at the Fed are banks and other financial institutions. Private citizens and businesses can’t open an account at the Fed. I tried, but they put me on hold.

Here is a simplified version of how it works, accurate enough for the present purpose. Acme Bank has reserves of $100 million at the Fed. During the course of the day, it makes loans and takes deposits. The loans end up as deposits in other banks. At the end of the day, all these transfers are “cleared,” meaning that if Acme lent a total of $20 million and received a total of $15 million, its account balance at the Fed would fall by $5 million, and other banks in the system would see their balance rise by a total of $5 million also.

I hope you didn’t tune out as soon as you saw numbers. Basically what is happening is that central bank money moves from one bank’s account to another to settle accounts with other banks.

Obviously, these bank reserves at the Fed do not take the form of piles of hundred-dollar bills. They are digital already. So what is new about CBDCs?

The novelty stems from the fact that the money you and I spend (with the exception of cash) is not central bank money at all. It exists only in the ledger of your commercial bank or other institution. If I Paypal you $1000, my Paypal balance and your Paypal balance change, but nothing happens in the central bank. Same is true if Alice, who banks at Acme, writes a $1000 check to Bob, who deposits it in XYZ Bank, and then Carol, who also banks at XYZ, writes a $1000 check to Dave who deposits it in Acme. These individuals’ account balances go up and down, but their banks are even with each other and the Fed is not involved at all.

A central bank digital currency essentially allows private individuals and businesses to have accounts at the central bank. It would function just like (and ultimately replace) cash, requiring no intermediary, no bank, no credit card company, and no transaction fee. If I buy a coffee at your cafe, an app or card reader sends a message to automatically credit your account and debit mine. The user experience would be the same as today, but there would be no fee and no lag time. Normally, paying by debit or credit card involves a 3% fee and a day or two for the funds to become available to the seller.

Attractions and Dangers of CBDCs

Now I’ll list some other benefits and advantages of CBDCs. You might notice that with a mere twist of the lens, many of these advantages take on an ominous hue. But let’s start with the positive:

-

As mentioned, CBDCs can remove what is essentially a 3% tax on most consumer-level transactions, allowing swift, frictionless transactions and transfers of money.

-

Unlike with physical cash, all CBDC transactions would have an electronic record, offering law enforcement a powerful weapon against money laundering, tax evasion, funding of terrorism, and other criminal activity.

-

The funds of criminals and terrorists could be instantly frozen, rendering them incapable of doing anything requiring money such as buying an airplane ticket, filling up at a gas station, paying their phone or utility bills, or hiring an attorney.

-

CBDCs are programmable, allowing authorities to limit purchases, payments, and income in whatever ways are socially beneficial. For example, all products could have a carbon score, and consumers could be limited in how much they are allowed to buy. Or, if rationing becomes necessary, authorities could impose a weekly limit on food purchases, gas purchases, and so on.

-

With programmable currency, citizens could be rewarded for good behavior: for eating right and exercising, for doing good deeds that are reported by others, for staying away from drugs, for staying indoors during a pandemic, and for taking the medications that health authorities recommend. Or they could be penalized for bad behavior.

-

Taxation and wealth redistribution could be automated. Universal basic income, welfare payments, stimulus payments, or racial reparations could be implemented algorithmically as long as CBDC accounts were firmly connected with individual’s identities, medical records, racial status, criminal histories, and so forth.

Basically, beyond facilitating transactions, CBDCs offer an unprecedented opportunity for social engineering. Assuming that those in control are beneficent and wise, this is surely a good thing. But if, as many of us now believe, our authorities are foolish, incompetent, corrupt, or are merely fallible human beings incapable of handling too much power, then CBDCs can easily become instruments of totalitarian oppression. They allow authorities:

-

To freeze the funds not only of terrorists and evil-doers, but dissidents, thought criminals, and scapegoated classes of people.

-

To program money so it can only go to approved vendors, corporations, information platforms, and so forth. Those that fail to toe the party line can be “demonetized,” with consequences far beyond what befalls the hapless YouTuber who utters heresies about Covid, Ukraine, climate change, etc.

-

Under the guise of rewarding good behavior and penalizing bad, to control every aspect of life so that it conforms to the interests of elite corporate and political institutions.

-

To nip in the bud any opposition political movement by demonetizing its leaders and activists, either with no explanation at all, or under flimsy pretexts that their victims would have no way to contest.

It boggles my mind that the public could accept such a momentous transfer of power to central authorities, with nary a whisper of democratic process. Something this significant should require explicit public approval in the form of a referendum, constitutional amendment, or the like, after long and considered public debate. Instead, elites discuss it as if it were an inevitability.

Art credit: Rachel Herbert

The Ideology of Progress

The elites who are preparing CBDCs are well aware of their totalitarian potential. I know this from reading their speeches and documents. Moreover, this awareness is not in the sense of a fiendish secret plot to gain totalitarian control and oppress the masses. Their internal narrative (among themselves and in their own minds) is more like the following:

Sure, this technology could be abused if it falls into the wrong hands. Thankfully though, it will remain in our hands: the hands of smart, rational, sophisticated people, well-educated in the best schools, who have advanced to the top of a meritocratic system. In fact, the Fourth Industrial Revolution that includes digital currencies and high-tech biometrics and surveillance will ensure that the good, smart, rational people will remain in power. These technologies will allow us to safeguard the world from irrational, anti-science, undereducated, psychopathic charlatans and demagogues who would mislead the masses and usurp the rule of science, reason, and technological progress. CBDCs will vastly expand our ability to rationally administer society for the net benefit of all.

As long as this way of thinking is firmly in place, then it matters little if Klaus Schwab and the elites are fiendish totalitarian plotters, or merely bland bureaucrats. The results will be the same. This ideology, whether they wield it as a cynical pretext or serve it with whole-hearted sincerity, will drive them to bring the whole world under their control.

We must understand CBDCs as part of a more sweeping ideology of progress, which celebrates any new extension of material and informational control. In that ideology, progress means improvements in our ability to capture the world through data, and to then manipulate the world accordingly. The more accurate and complete the data set, the better able we will be to improve human life. The old policy-making standard of the cost-benefit analysis can be automated through AI algorithms that maximize whatever the smart people in charge choose as the appropriate metric of well-being.

“The more accurate and complete the data set, the better able we will be to improve human life.” Thus it is that CBDC scenarios normally include the ideal of a cash-free society. Cash transactions are outside the data set. They are hard to monitor or control. For CBDCs to fit into social engineers’ paradise of total control, they must accompany the elimination of cash.

This whole program depends on unconscious assumptions: that everything important can be measured, that everything real can be quantified, that every causal principle can be known. The program’s operators seldom consider what—and who—gets left out of the metrics.

Beyond the Binaries

Returning now to matters of currency, I’d like to add some complexity to the dystopian possibility I’ve described. Under apparently binary distinctions like centralization/decentralization, freedom/control, and politics/economy, other principles lurk unnoticed.

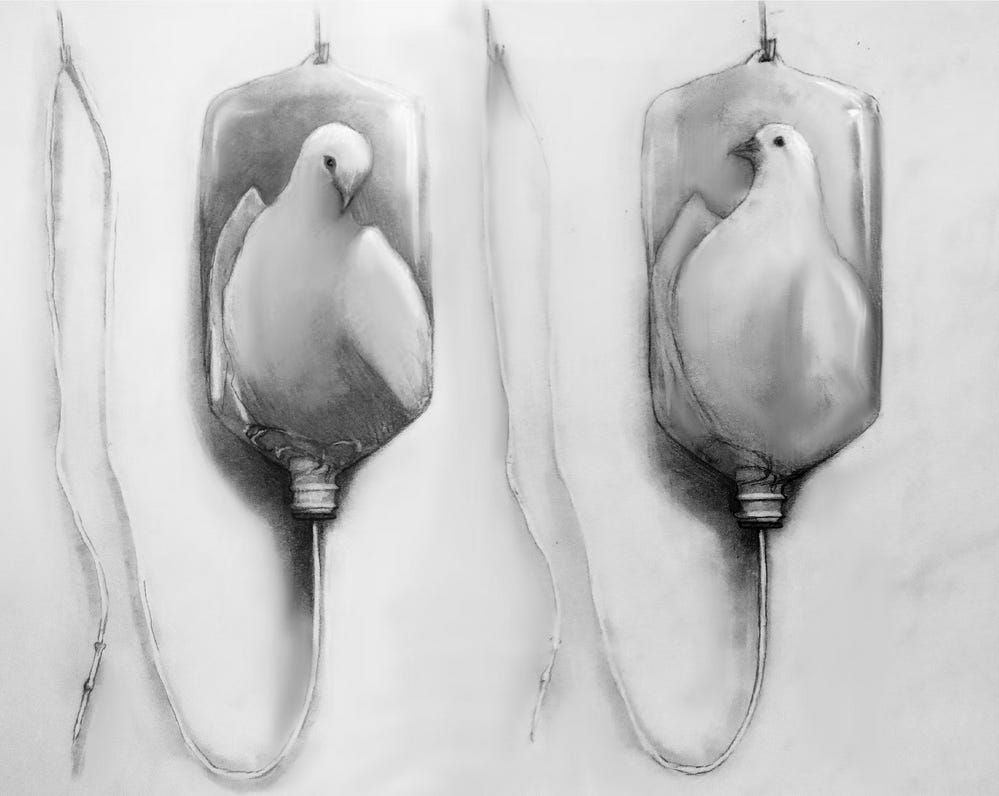

Art credit: Natasza Zurek, Dualistic Nature

It may look like CBDCs are qualitatively different from money today; that they are more like rations stamps. Real money, one supposes, can be spent on whatever one likes. Real money, one supposes, is fully alienable from its owner. My dollar is the same as your dollar, and it bears no trace of its origin. All that is true of cash, but is not necessarily of programmable currency. Is it money at all?

The notion of money being free from political interference brings up a more general issue: the relationship between the economic and political realm. Communism obliterates the distinction and unifies the two. Libertarianism seeks the reverse, to banish politics from economics. In practice, the two have never been fully united nor fully separate. Both money and government are modes of human agreement.

The libertarian ideal of money that is outside political interference is based on a misunderstanding of money’s historical origins. Long before the first coins were minted in Lydia and Greece, complex societies kept tallies of contributions to granaries and temples, tallies which could then be used as the basis of lending or exchange. In other words, money originated as credit, not cash. It originated as a social recognition of contribution, not as fungible commodities replacing barter.

Even after the advent of coinage, many or most transactions were settled via credit. In the Middle Ages, records of who owed what to whom were kept on ledgers and tally sticks, and settled only occasionally with coinage. In that context, one person’s thaler or shilling was not equal to another’s. Merchants were much more likely to accept the IOUs of people of “good account” than they were of the town drunkard. One might have good credit in some quarters and poor credit in others. In that sense, money was similar to certain CBDC proposals: It could not always be spent equally everywhere, and was not fully alienable from its source.

Do not interpret the above as an endorsement of CBDCs. There is nothing wrong with social accountability in money, but it needn’t come from central banks and governments. Two issues are at stake here: the degree of political influence over the economy, and the agent of that influence. The degree ranges from an individualistic free-for-all at one extreme, and minute control over all earning, investing, and spending on the other. The agent of the influence could be a centralized state, or it could be some other social structure(s).

Money bearing the characteristics of cash (anonymity, alienability) inherently curtails the power of government, and indeed any form of social control. Not all societies hold limited government to be a good thing, but the United States was founded on it as an ideal. One way to limit government’s power is through a system of checks and balances. Another, complementary, way is to keep realms of human life outside government purview—to maintain a realm that is unregulated, non-juridical, undefined. This does not leave it as an individualistic free-for-all. It allows the operation of other modes of human social regulation. These include community, morality, consensus, extended family, custom, tradition, and cultural normativity.

In classical leftist thinking, the state is distinguished by its monopoly on violence. In a court of law, the losing side must abide by the court’s decision, or ultimately armed officers will en_force_ it. The colonization of community and informal culture by law is in that sense a colonization of life by violence. It shifts more and more of the edifice of culture onto the foundational bedrock of violence.

How Healthy Societies Constrain Money

The modern decline of non-monetized modes of social organization (community, morality, tradition, extended family, etc.) leaves only the legal system to check the wanton abuse of money power. From ancient times until quite recently there were extra-legal social limits on the free spending of money. The wealthy would suffer social pressure if they were too ostentatious or failed to uphold civic responsibilities. As communities weakened, so did these social pressures.

I remember a story I read as a child from one of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books. Deep snow had cut off the frontier town from the outside, and its grain supplies were running low. Finally, someone managed to make a run through a blizzard to bring in a cartload of wheat on behalf of a local merchant, who for a few weeks became the town’s only supplier. At first, he tried selling the grain at a huge markup, but when the citizens indignantly explained to him that he would be shunned forever more, he relented and sold it at cost.

In those days, people depended on each other in a network of gifts, favors, and obligations. An intangible civic currency circulated along with the financial currency. It enabled people to hold each other accountable. Money would not have done the merchant much good if the town’s doctor, laborers, carpenters, teamsters, and so on bore him ill will and refused him service. That is what might happen to those who offended local mores.

Not to idealize those times, one must also point out that these mores also encoded all manner of racist and sexist attitudes. Even people who bore no racism themselves might still participate in redlining, segregation, and other forms of discrimination, because the social consequences of flouting these conventions were severe. Racist laws were but one layer of the edifice of Jim Crow. But I digress. My point here is that state power was not the only limit to financial power.

Just as checks on government power are essential to a wholesome society, so also are checks on economic power. In the modern age, little remains to check it outside the state (or more precisely, centralized authority). State and money together have usurped nearly every other mode of social organization. When centralized authority subjugates money and property, we have communism. When money and property subjugate the state, we have oligarchy or fascism. Both lead to the same end: the fusion of economic and political power, and the totalitarian domination of all aspects of life.

Those who quite rightly criticize CBDCs for their totalitarian potential must understand that anonymous, trustless money (cash, and today, certain cryptocurrencies) is also antagonistic to a healthy society. I personally would prefer it to total state control, but there is a reason why drug dealers, child pornographers, extortionists, and other criminals use it. It allows them to violate social norms. Historically, cash prevails during times of war and social turmoil, when social structures have ruptured, strangers show up, and people don’t trust each other. (See David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5000 Years for a compelling argument.) When things settle down and durable social structures emerge, then cash gives way by degrees to credit.

The problem today is not, as the central authorities see it, that too much economic activity lies outside their ability to track and control it. Nor is it as libertarians see it: that individual freedom is eroding away. As in most polarized debates, both sides tacitly accept the very circumstance that generates the conflict to begin with: the erosion of civil society structures that hold people accountable for their actions.

In fact, most people do not want the kind of freedom that is oblivious to the effect of their choices on other people. How do we know whether our economic choices do good or ill? In a healthy society, a myriad of feedback loops inform us how our choices land on others, and so help us navigate life. The CBDC vision relies instead on central authorities to tell us, and to program that information into money so that, for example, products with high embodied carbon become more expensive.

If this were the only conceivable source of social and ecological accountability, then maybe we ought accept the central control and do our best to improve its character. But there is an alternative to subjecting ourselves to the dubious wisdom of an (at best) paternalistic or (at worst) predatory state. We can build and rebuild other systems of social accountability.

In other words, the answer to the threat of centralized totalitarianism is to build community: traditional place-based community as well as online community.

Here we come to the issue of decentralized digital currencies. But before commenting on them, I want to clarify that an economy is not the same as a community, and a community is more than a network of people. A community is a group of people who need each other. Obligation and gratitude, giving and receiving bind them together. Community wanes as financial affluence waxes. If you can pay for everything, you don’t need anyone. The more we meet needs through money, the more vulnerable we are to financial collapse and to control though CBDCs. If the government cuts off my access to money (for example, because I post “disinformation” on my Substack channel), I will be incapacitated if I’m completely dependent on that money to meet my needs. But if I am well embedded in networks of gift and trade, if I grow some of my own food, if I have shared generously over the years, if I have people around me whom I needn’t pay to meet my needs for food, child education, music-making, home repairs, medicine, and care when I grow old, then I will be at least partially insulated from state power. This is a kind of autonomy that alarms fascists and communists both (both flavors of totalitarian are deeply suspicious of any form of social organization outside their purview). Yet it seldom occurs to libertarians either, who normally think in terms of autonomous individuals.

Well, there is no such thing as an autonomous individual. The true nature of the human being—indeed, of being itself—is relationship. Only a system built upon that metaphysical understanding can hope to durably fulfill the hopes that we invest in it.

There is no such thing as an autonomous individual. We are creatures of dependency to the core. Let us not speak, then, of freedom from social constraint. Let us ask instead how we should be constrained, and by whom. To whom should we be accountable, to whom should we be in debt, on whom should we depend in our neediness?

Society as Organism

In addition to non-monetary structures of mutual support, other forms of money also grant a degree of insulation from CBDC control. CBDCs are not so scary if they are not the exclusive permitted form of money. If only a portion of economic activity is transacted in CBDCs, the situation is little different than it is today. Already banks and other financial institutions do the government’s bidding in terms of providing transaction records or freezing bank accounts, as the demonetization of Wikileaks demonstrated already in 2014. In the dreams of totalitarian idealists, no financial activity exists outside their surveillance and control. That is why governments around the world are pushing to eliminate cash and outlaw, or at least regulate, cryptocurrencies.

In fact, cryptocurrencies already provide some of the advantages of CBDCs. For example, second- and third-generation cryptos allow instantaneous transfer of funds at nearly zero cost (and low energy consumption). The technical challenges of transaction time, scaling, and energy use have largely been solved. The socio-political questions have not, and here is fertile soil for the cultivation of new forms of social accountability and new ways to infuse values into money.

Bitcoin maximalists criticize other cryptocurrencies for not being truly decentralized. In most cases, the currency’s founders or a small group of nodes and developers wield strong influence over policy decisions, such as whether to modify the protocol. Theoretically, this leaves them vulnerable to government pressure. A fully decentralized crypto is like cash in the age of precious metal coinage. No one is in charge of it. No organization or group has a determining influence on it. Its value is (supposedly) independent of human politics.

Is that a good thing, though? If the only consideration is government interference, then yes. If we would like to encode money with social, moral, or ecological values, then no. Many newer currencies make a virtue out of their semi-centralization by building some form of community governance into the protocol. Yes, this might make them vulnerable to manipulation by central government authorities; on the other hand, they can nucleate the formation of new centers, parallel structures outside the state.

In a corrupt age, it is tempting to cede control over money to an impartial, impersonal algorithm to insulate it from the messiness of human politics. Ultimately though, politics (in the broad sense of agreements among the human collective) must subordinate money, and values must subordinate value. Do we really want to create money that we cannot change, and risk loosing a Frankensteinian monster upon the world?

It is much better to build governance of money into money itself. Instead of pure decentralization, in which there are no power centers at all, we might think more fruitfully in terms of multiple centers in an organic structure. An organism does not a have a single command-and-control center. Yet, neither is it a mass of undifferentiated co-equal cells. The brain, the heart, the endocrine organs each have systemic influence, but none supersedes the others. They are mutually influencing and mutually dependent. There is a reason that bodies (and ecosystems) grow that way: It makes them adaptable and resilient.

The main threat of CBDCs does not lie in those currencies per se. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with socio-political influence over money. The danger is that they will become the only money, as power-hungry central institutions ban cash and cryptocurrencies to fulfill their dreams of total control. We need other centers of power, other centers of social influence, accountability, and agreement, and other financial organs. Without them, tyranny is inevitable, CBDCs or no, and ideals of individual freedom will not stop it.

We cannot rely on the state to create other centers for us; we must create them ourselves, and protect them from central institutions.

These new structures can embody positive values. In the last few years lots of crypto projects have come across my desk that attempt to integrate social and ecological values into their design. Some are already doing some of the things that CBDC planners envision, such as incentivizing certain behavior. It could be participation in a community, engaging in climate action, or removing plastic from the ocean. At least one cryptocurrency, Celo, is carbon-negative by design (through investing its funds in ecological protection and restoration). It is also part of a growing ecosystem of protocols that support community-building and the development of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). Many of these also incorporate various kinds of democratic decision-making and self-governance into their protocols.

Crypto is still an immature technology, a technological experiment, used by perhaps one percent of the population. It is rife with greed, deception, and get-rich-quick schemes, often disguised in lofty ideals. Some of the issuers who claim ecological values are merely engaging in ecological virtue signaling. Nonetheless, for all their problems, cryptocurrencies and their surrounding technologies illustrate the possibility of incorporating social values into money and developing participatory social structures that are independent of the state.

To fight the system is futile if one cannot offer an inspiring alternative. What is the alternative to a machine-like society centered around an all-seeing, all-powerful CPU? It is society as organism, society as ecosystem.

For that, we need to grow new organs and revitalize those that have withered. The withered ones include place-based communities, local economic structures and civic organizations, a culture of reciprocity and mutual aid, local earth-based skills held collectively and generationally, and extra-legal practices of conflict resolution. By revitalizing the in-person and the place-based, we become resilient to the encroachment of technology and all things digital. Secondly (and, I would say, secondarily) we can grow new organs in the digital realm.

The stronger these new and revitalized organ systems are, the less CBDCs will matter, as money and power devolve away from the center. The ultimate goal cannot be to eliminate national and global scale governance entirely. After all, some of our problems and creative possibilities are national or global in scope. However, because economic and political power is presently far too centralized, we should halt the rush toward CBDCs and focus our attention on other organs: the local, the bottom-up, the informal, the peer-to-peer.

What is really at stake here is the reclamation of something we could actually call a society. Indulge me while I exercise a special sense of the word. A true society is not a collection of atomic individuals ordered and directed by a central power. Originally, the word connoted fellowship, companionship, alliance, and friendship. Central authorities, however beneficent, cannot grant that to us. Their intervention may, arguably, be necessary if life devolves into a war of each against all. CBDCs and the rest of the surveillance state are symptoms of devolution as much as they are causes. It is up to us to reverse it. It is up to us to begin walking the long road back to fellowship.

Charles Eisenstein is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider making a donation. Thank you.